A map is a coded compact representation of reality, and coding means making choices, classifying, and simplifying many layers of information. Any choice that is made in the context of the territories shown is political. As such, a map can never be neutral. Considering that maps play a regular role in the discourse that shapes our world, the making of them should be constantly critically examined. Which authority draws the lines? What really defines our borders? Do geographic boundaries limit our territories, or are they specified by the speed of the internet, tax havens, war, piracy, Google, Ikea, or our holiday destinations?

The methodology of subjective mapping opposes the top-down, seemingly objective cartography position. Instead, it aims to counterpose the purported neutrality through engaged mapping projects. To this end, it proposes a bottom-up approach of mapmaking by inhabitants (subjects) themselves, which allows them to question dominant ways of representing territories and demystifies standard methods of mapmaking. In so doing, the subjective Atlases offer a platform for collective visual dialogue to challenge the social, political, and cultural circumstances of our day-to-day realities, which potentially contributes to more pluralistic and sensitive territorial identifications and experiences.

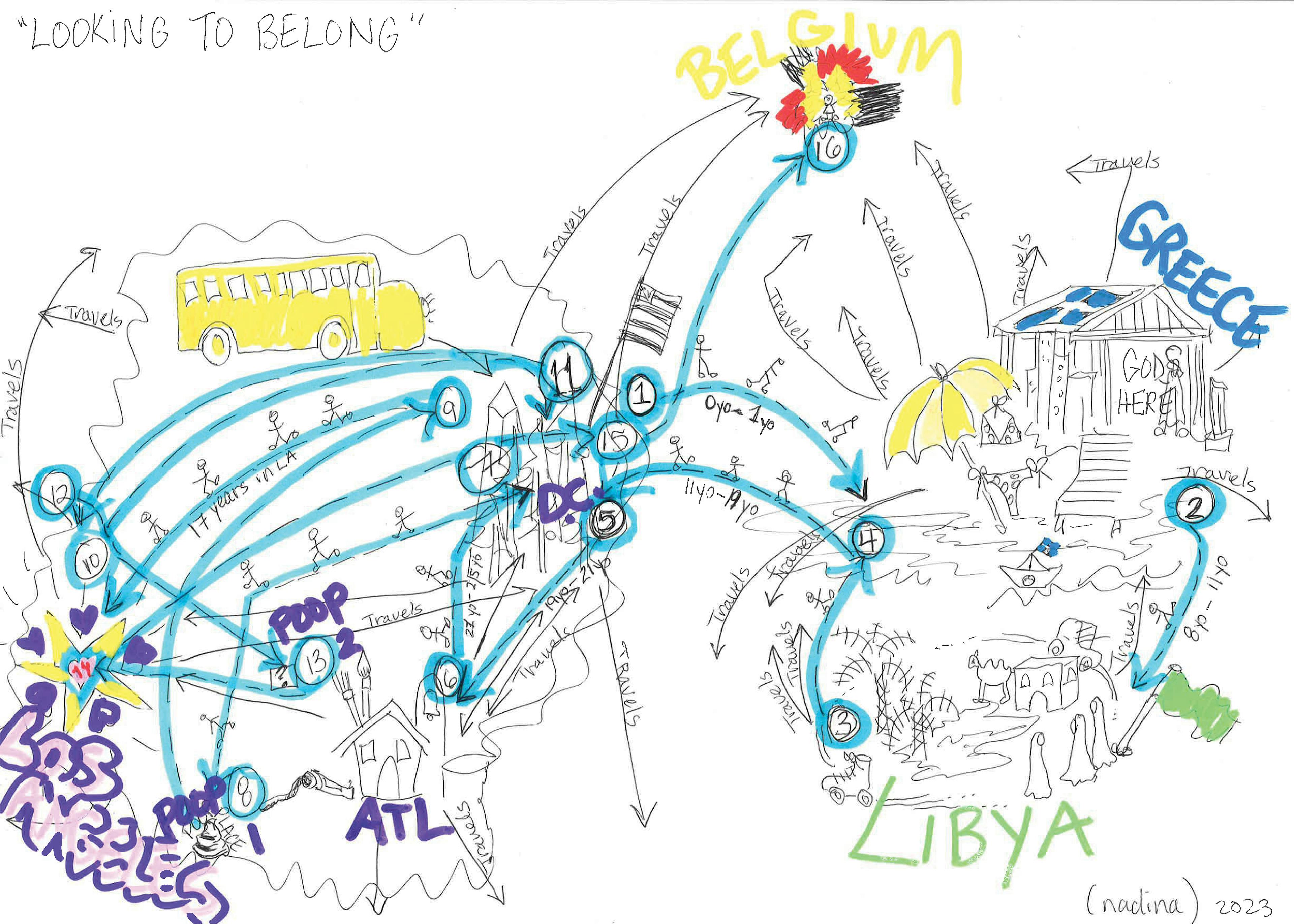

Draw your own ‘migration route’

Given the above aim and perspective, participants, i.e., people with a migration background, for which this briefing is principally intended, are invited to map their migration route from their own political, critical, romantic, negative, or positive experiences. What participants consider as a route is up to them. And it is up to the participants to visualize what they feel comfortable sharing as long as it fits on one A3 paper.

Discussing the migration routes, Maplab by Annelys de Vet, 2023

Looking to belong’, Nadina Embrey, 2023

The flag is the political symbol par excellence. It is a sign of power used to claim territory and to visualize the imagined homogeneity of a country. In that sense, it is the equivalent of the state borderlines on the standard political map. In reality, however, countries are much more diverse due to cross-border mobilities and influences than the top-down flag suggests. To deconstruct the singular meaning of flags, and challenge their top-down uniformalization, participants are invited to design their own flag beyond predefined borders. What kind of flag could represent the crossing of several states, and how can a flag be personal instead of universal?

To put it in a question:

If your migration route would be a flag, how would you then visualize this? And what title would you give your flag?

Impressions of the alternative flags, Maplab by Annelys de Vet, 2023